Measuring Angles with FMCW | Understanding Radar Principles

From the series: Understanding Radar Principles

Brian Douglas, MathWorks

Learn how multiple antennas are used to determine the azimuth and elevation of an object using FMCW radar.

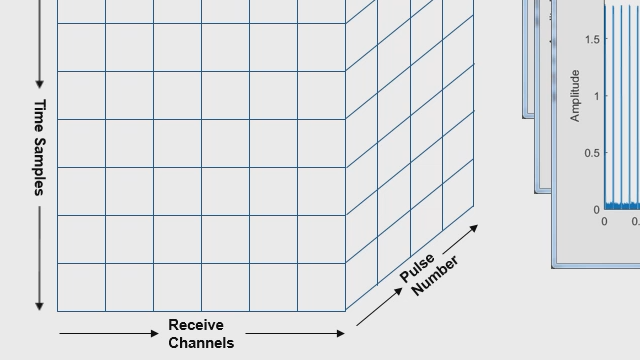

By looking at the phase shift between the received signals of more than one antenna, the direction to an object can be determined. The accuracy of this measurement depends on the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the radar system. Increasing the number of elements in the antenna array increases the angular resolution of the radar. With multiple transmit and receive antennas, a virtual array can be created which can produce the same resolution with fewer overall antenna elements.

Published: 13 Jun 2022